Observed in most developed countries, this "U-curve" polarisation raises fears of atrophy of the middle class, a rise in inequality and a brake on social mobility. The causes of such a phenomenon remain a matter of debate: the overall increase in the level of qualifications favouring the most qualified, automation, outsourcing, offshoring, and enhanced flexibility would reduce the need for lower-skilled workers and employees. Furthermore, the increased rate of participation of women and immigrants in the labour market would further expand the personal services industry. But before we look at the causes and effects of polarisation, we must first have to ask ourselves if this diagnosis is an accurate assessment of the French labour market.

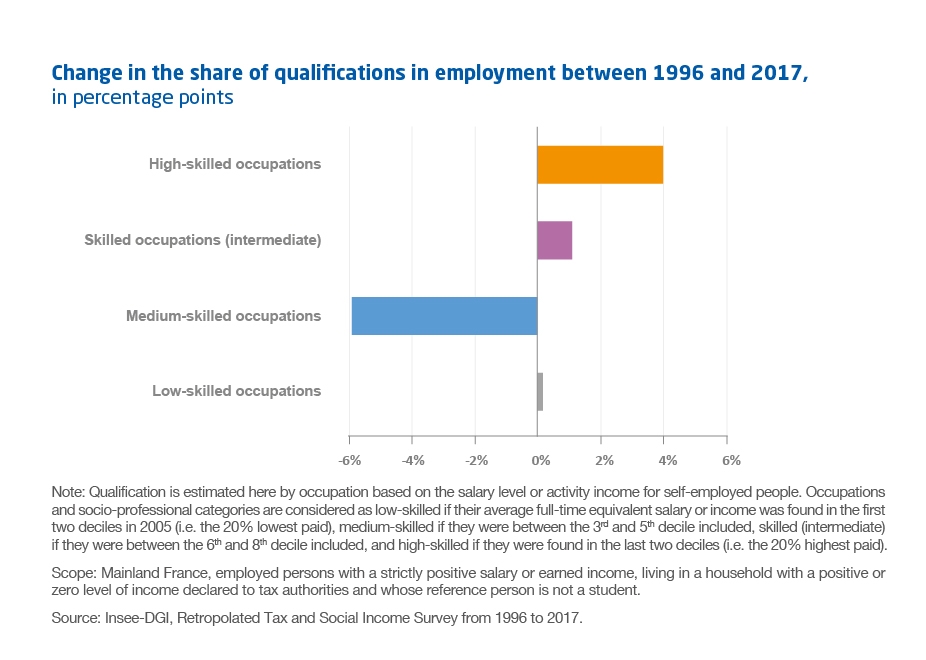

To achieve a more precise vision of the matter, we will need to dive deep into the world of statistics. Whether we approach the question either through socio-professional categories, individual wages or the average wage level of occupations, we would always come up with the same outcome: while there is indeed an erosion of median qualifications in favour of executive occupations, we do not observe in the case of France any increase in the share of low-skilled jobs. In contrast to the already abundant academic literature on the matter, the INSEE and DARES statistical institutes' detailed analyses confirm this more nuanced diagnosis for France.

Conflicting diagnoses are mainly due to methodological challenges: the selected scope of the active population, the availability of data over a long period, inconsistent classifications of occupations – sometimes involving cultural differences in defining skilled and unskilled occupations, all these variables influence the conclusions. Thus, the challenge is a technical one, and the issue is particularly crucial, as public policies must be based on an accurate appreciation of the labour market evolution given the Covid-19 crisis, which could certainly structurally disturb the market.